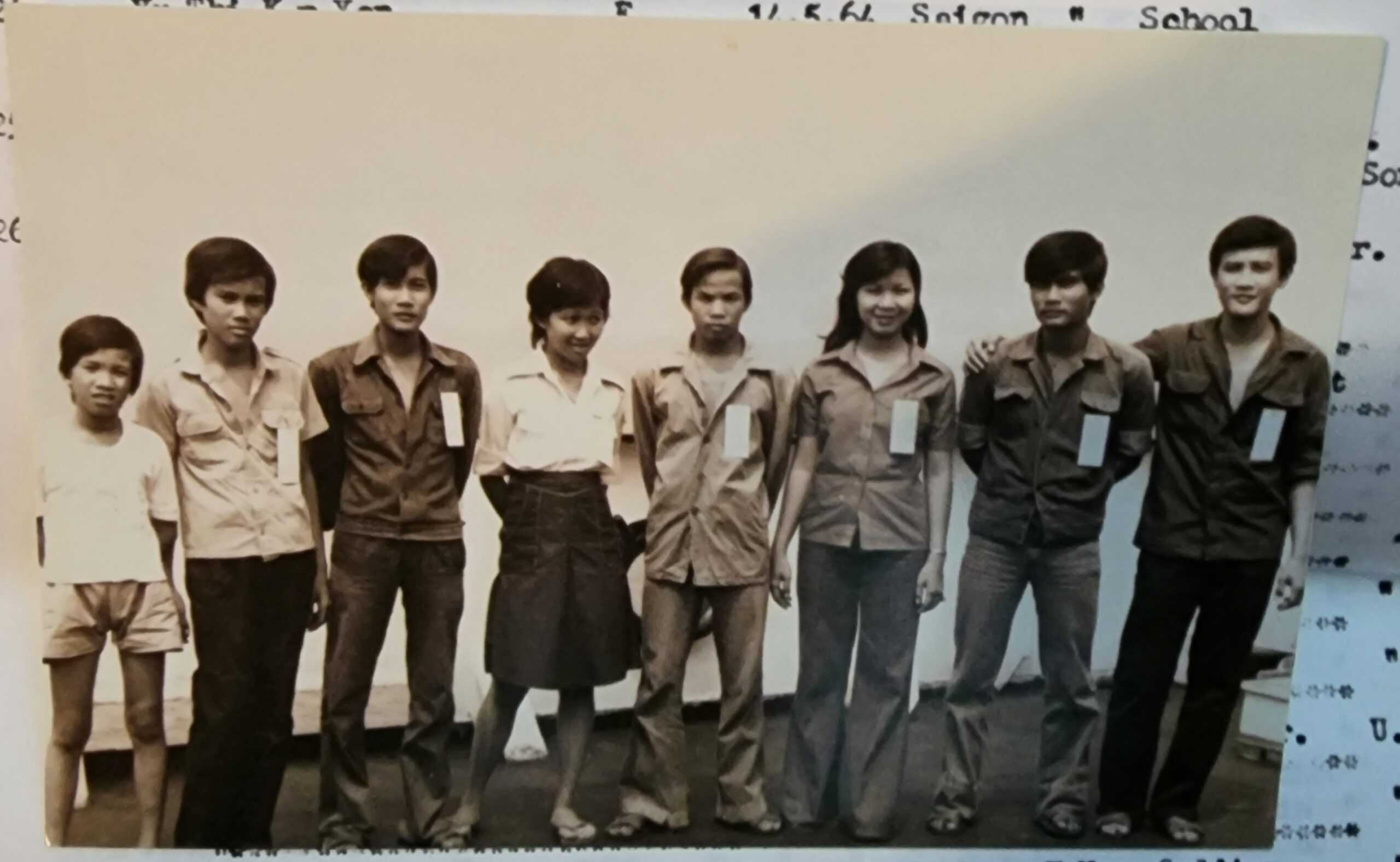

Posted: October 7, 2024

I started writing this story on my dad’s last day of work in 2024. That day, he passed on his engineering skills to a younger employee. He has worked in America for 40 years. That’s two-thirds of his life! He almost died coming to America on a rickety wooden boat on the ocean. Read on to see why he would do such a thing.

Table of Contents

What Was So Bad About Vietnam After the War?

Just because the Vietnam War ended didn’t mean citizens weren’t suffering. In fact, postwar Vietnam was worse off for many people.

A communist curtain draped over the Vietnamese people. They suddenly felt a chokehold in their lives. Any Western media, like BBC Radio or your favorite ABBA album, were illegal. Food rations were too few, with people waiting in line with food coupons, only to learn during their turn that there wasn’t any food left.

If hunger wasn’t enough, people were living in constant fear. Because they had to be on guard around everyone in the neighborhood, they got weary and nervous from the constant suspicion. It was a burden on the mind to know at any time, you could be questioned, criticized, interrogated, and jailed out of baseless suspicions that you were a traitor to Uncle Hồ Chí Minh. A kid could call you out. An officer could see your attitude or even your appearance as improper of a communist citizen. Drove too fast? That one officer didn’t like your blue shirt for whatever reason? Too bad, mate.

This is how, in Sài Gòn, my dad had an unplanned stop at the barber because an officer on the street thought his haircut was a menace to society. It should be cut as Uncle Hồ would have wanted it. I doubt while he was alive, Uncle Hồ would have worried about haircuts when he was trying to fight against an imperialist world power that was America. Nah, that officer just used Uncle Hồ’s name to abuse his powers against innocent people like my dad for having an “improper” haircut. Imagine how awkward it would have been walking into the nearest barbershop to say, “Hi, I’m only here because that soldier told me my hair was too long. I would appreciate a trim so the solder can return my ID.” My dad wouldn’t have said such words, but he could have been thinking that!

At its worst, my dad had to go into hiding, living with his powerful Communist uncle while his parents and two younger siblings were sent to a southern reeducation camp near Sóc Trăng. This was retribution for my grandpa, who served as a nurse in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). He was brutalized to the point of starvation, his ribs peeking out from his chest. But he was just a nurse. High-ranking officials, like my mom’s dad, died in an even more brutal northern camp. Years later, my mom’s siblings visited the camp, only to find a pile of bones.

As the oldest son, my dad was the one with the most potential to build his career for his struggling family. But the young fellow had no future in his homeland. Postwar Vietnam had no opportunities for him to advance in a professional career. If anything, he lived his life in a reactionary way, which wasn’t healthy for any young man. Who knew if another officer would come by and send him to jail for any reason? What was the point of living in constant fear, ever vigilant of being accused, sent to jail, or even killed? This was hard on everyone, especially young people who were ready to have a future but were denied the chance.

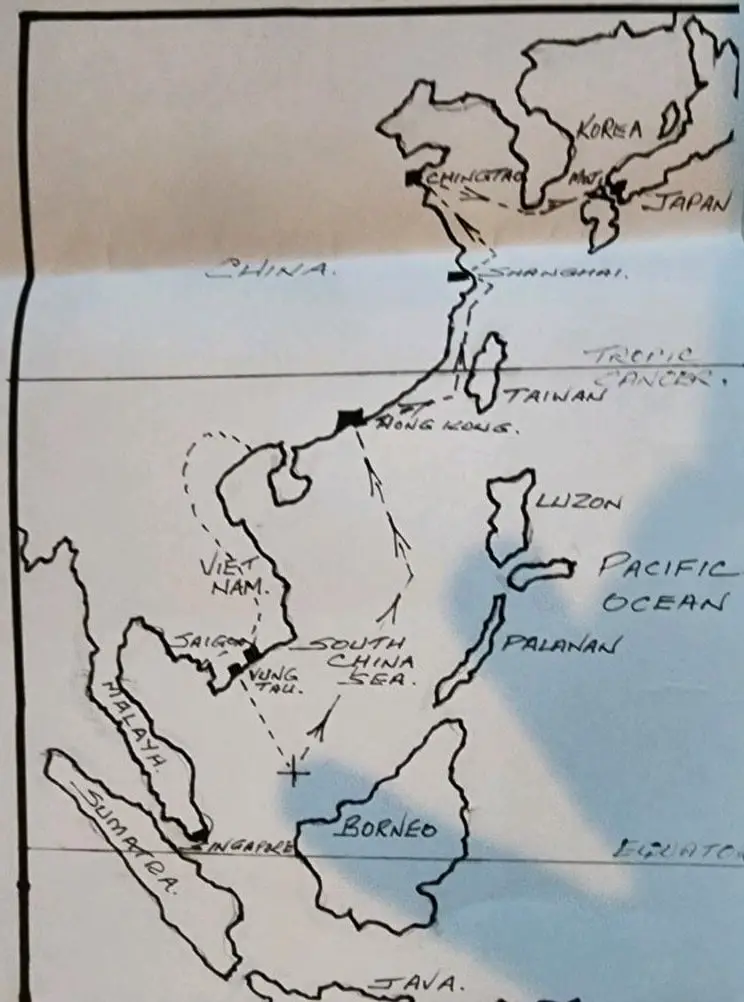

This is what drove almost 800,000 Vietnamese boat people out to sea between 1975 and 1992, the peak reaching over 100,000 people (including my dad and uncle Thi) in 1979. They would rather die trying to escape than live a life of fear and uncertainty. As far as they were concerned, they were already dead in their own country. Leaving to uncertain seas couldn’t get much worse. Unfortunately, most people died at sea.

An uncle of mine died this way. One night, when my mom was 18 years old, her older brother, Mẫn, visited her in a dream. He had escaped Vietnam by boat 2 months ago, and his family had never heard back from him. In Mom’s dream, she was standing on the shore while Mẫn’s half-naked body slowly rose out of the water up to his waist. He was soaked, water from his hair dripping down to his chest. Behind him was a sinking boat, the stern tilted down. He walked toward Mom in waist-high water. “You’re home! You’re still alive!” she said. Mẫn nodded his head no before saying, “I fell against the propeller.” As if demonstrating his fate, his body slowly sunk back down into the water to never be seen again. My mom woke up in a panic and rushed to tell her siblings the sad news. The pain of escaping hurt for the people left behind just as much, maybe even more, than the escapees themselves. I know Mẫn is at peace now.

Escaping was a tricky, expensive business. Conmen made a living out of cheating hopeful escapees by charging them lots of money to have a place onboard a boat. There was no accountability. The boat may not have existed. My dad’s family failed to escape several times because no agent or boat arrived at the agreed rendezvous point. Dispirited, my family gave up and faced a hopeless destiny in Vietnam, poor and scouring for income under government scrutiny.

The Final Escape

But my uncle and dad kept trying. Their mom paid for this last attempt with gold sheets. One day, an agent led the two men to Sài Gòn’s Y Bridge. They hopped on a canoe so flat, it was a wonder that water didn’t flood over with each wave. The canoe’s tiny engine putt-putted on the Sài Gòn River through the Cần Giờ delta in complete darkness. The agent knew exactly the narrow rivers to take through the sinewy mangrove forests and where the fishnets would be raised to prevent entanglement. But still, my dad was so scared of the unknown lurking in the dark. His racing heart was beating hard for fear of being caught by the police who could arrest them. But they sailed through without being noticed. I believe this was where my father’s lifetime fear of the dark came from. For years, I have wondered why he felt anxious in the dark, believing he couldn’t carry out the task unless he had a flashlight. Most recently, I complained about the lights he installed in the trunk of our car, which may accidentally turn on while I’m driving at night, making it hard to see behind me. But as always, he insisted the lights stay!

In some secret place in the mangrove forest, they were moved to a riverboat, which wasn’t built for the open ocean. It was a leaking hunk of wood that just so happened to have an engine that was barely running and always needed fixing. But it was the only boat they had. The other problem was that the little canoes were bringing only customers, no fuel or water. But they couldn’t refuse those people. Anyone could scream, get the authorities’ attention, and screw up the whole operation.

You could say this plan wasn’t orchestrated well. It wasn’t. It was too last minute because the organizers’ original boat got caught. But they couldn’t back out. They were too far into this mission. So off it went, that overloaded boat of 132 people without much fuel or water. It left the Cần Giờ delta for the open South China Sea at about 5 AM. My dad saw his last sighting of Vietnam: people exercising under the city lights of Vũng Tàu in the wee early hours of the morning.

44 years later, my dad and I were riding a commuter ferry, following the same path from Sài Gòn to Vũng Tàu. A common cold gave me a lovely sore throat, cold chest, and congested nose, but I couldn’t really complain after knowing what my dad had already gone through four decades earlier. I swallowed whatever ickiness was building in my throat and carried on, watching the gleaming skyscrapers of Sài Gòn disappear. The ferry itself, though loud from the heaving engine, was a pleasant scenic ride past thick mangrove forests and over the river the color of the earth. Modern indoor seating, complimentary water bottles, and rice crackers helped the time go by. The one flatscreen TV played, in order, Leo Sayer songs with kissing couples, candid comedy videos involving cars and camera victims, and muscular people swinging and leaping their way through an American Ninja Warrior obstacle course in Atlanta. Perhaps the romantic Leo Sayer songs were the most appropriate, even if a bit showy for the kids, for a scenic ferry ride with a bunch of tourists, both Western and Vietnamese. However, I preferred watching people getting into parallel parking accidents and drunk wedding couples falling over their feet. I tried to ignore my boredom snatching up trash TV and instead watched my dad notice the mangrove forests he had never seen by day until today as a tourist riding in comfort. Peering out the window, I imagined Dad’s little canoe trailing behind our comfortable, cushy ferry.

As our ferry docked near Vũng Tàu’s Front Beach, I stared out onto the open ocean, imagining a wooden fishing boat, so delicate, so tiny, piercing through the waves endlessly and aimlessly, like a child pushing a toy boat in a bathtub. The fishing boat was cast adrift at sea. Aimless, nowhere to go, no direction in mind, at the mercy of the winds and currents. A tattered sail meant that they couldn’t harness the wind. It’s not like this boat was meant for ocean voyages anyway. The supposed navigator didn’t know squat about navigating boats. He claimed he was a navyman (he was actually just a landlubber musician) just to get a spot on the boat. I’m sure some fellas thought that throwing that faker overboard would be a great night’s entertainment, but he had a wife and two kids, so that was the end of it. The most qualified sailors would be the fishermen, but they were only that, fishermen. They didn’t know how to cross the ocean.

I wonder what the refugees might have thought seeing Vietnam disappear from view.

I may never see Vietnam again.

I had better get my family overseas if I survived this godforsaken trip.

Oh crap, did I forget to turn off the stove? (I doubt this one, but hey, you never know.)

The boat left in such haste that it was inadequately supplied. Fuel and food ran out on the first day. It was the only day people were using the makeshift toilet hole at the stern of the boat. Without enough food and water, they stopped using the toilet.

The boat people’s throats itched for water, but they couldn’t have a drink of the saltwater surrounding them. It was as if the water taunted the pitiful humans who chose to place their lives at the mercy of the sea. Baked by the sun but surrounded by water. The same water that lifted the boat high, high, high up into the air on monstrous waves, which then dropped and slammed the boat against the sea. It was a fragile boat, but luckily not fragile enough to be snapped into two. Other people were seasick, but not my dad. He was blessed like that.

On the 5th day at sea, one of the organizers back in Vietnam heard a BBC Radio broadcast about a U.S. Navy plane detecting a potential refugee boat out on the open sea. This very well could have been my dad’s boat! A plane did, in fact, circle around over the boat. The boat people signaled to the airplane. The pilot shook the plane back and forth to acknowledge the boat. Seeing that the boat people were in distress, he dropped down a package, perhaps a survival kit. But Santa’s gift landed too far away for the boat people to swim and retrieve. There was an emergency gallon of fuel, but Santa’s gift wasn’t worth it.

Santa continued trying (“trying” is the key) to be a helpful fella. He pointed his sled in a specific direction. He tried to give the boat people a bearing to Malaysia, Indonesia, or wherever it was. But one gallon of gas and inexperienced fishermen weren’t going to get them there. From his sled, Santa might have alerted commercial ships in the area about the boat. If that happened, no one cared because no one came for them. So, as exciting as it might have been seeing a plane, it was a false hope more than anything.

The Rescue

On the morning of the 11th day at sea northwest of Borneo, my dad thought he would die on his 20th birthday, August 4, 1979. But wait! There was something in the distance! Oh yes! There was a ship only half a mile away! As if it were some movie miracle, the boat people used their last gallon of gas to haul ass to this ship summoned by heaven.

This was a British cargo ship called the Ruddbank, and it was on its maiden voyage from Bilbao, Spain to Shanghai. But it wasn’t enough to be seen and hope for a rescue. Without an accident at sea, the Ruddbank could look away, as many ships have done with other boat people out of compassion fatigue. But the rules of the sea said that people must be rescued if in a maritime accident. So the boat people created the “accident” by crashing their boat into the Ruddbank’s side, suicidal kamikaze-style, hoping to force a rescue.

Except they didn’t crash. The cargo ship’s wake was sending huge waves against them, so the boat bounced back from the waves like a little bathtub toy. So much for the kamikaze. They couldn’t kill themselves if they wanted to.

But being close enough worked. The Ruddbank crew thought they had accidentally run over the cute little fishing boat. And so they reserved the ship. Very slowly. And without waves! That’s when the boat people took advantage of this and finally crashed into the starboard side of the Ruddbank. The Ruddbank crew could really see, then, that there was an “accident.” One of the fishing boat’s walls came apart, so water was seeping in. Time for a proper rescue!

The Ruddbank came just in time. The wooden boat looked like it carried a pile of dead bodies with arms and legs sprawled across the deck. Actually, the refugees were alive, but barely. Almost everyone, including my uncle, was too lethargic from lack of nutrition.

When the Ruddbank dropped a rope into the sea, my dad’s helpful instincts from the Boy Scout days kicked in. He was one of the few people who had enough energy to move around. As he dived to fetch the rope, he thought to himself, If not for this rope, we could die. This is the rope back to life. With the two boats tied together, the boat people started to climb the rope up to the Ruddbank, pushing and shoving along the way. As my dad stood back on the wooden boat, he was appalled at the animalistic nature of these desperate people, as if they would die by spending another minute on that rickety boat.

They set the wooden boat ablaze to destroy it since floating flotsam could endanger other ships. My dad believes the wreckage is still floating somewhere on the ocean’s surface. Wood never sinks.

124 people were brought safely up. Sadly, a 3-year-old toddler named Le Minh Hieu was already dead by the time he was brought up. His mother was so faint that she didn’t even know about her son’s death. That night, a 2-year-old baby, Bui The Linh, died in the captain’s quarters after desperate attempts by the Ruddbank crew to save him.

On that day, my dad didn’t just turn 20. He was reborn into a new life. He vowed not to waste this second chance at life. He told himself from that day on, he wouldn’t be a slacker. He couldn’t. Instead, he had to work hard and become successful by advancing the ranks of society.

The remaining survivors spent weeks on the Ruddbank. It may be a big cargo ship, but suddenly, 122 people come on board, and room must be made for the new passengers! The refugees dined with Bangladeshi and Indian sailors, eating delicious beef curry.

Some refugees helped around the ship, especially when some sailors got seasick. They washed dishes, cleaned the kitchen, and mopped the floor. The best place to work, according to Dad, was the officer’s kitchen near the bridge. Not only was it clean, but it felt like you were on top of the world with elevated views of the ocean opening out across the globe. Not that there was much to see besides a whole lot of water. But it must have been nice to catch a sweeping view on the most solid ground since leaving Vietnam. As a treat, the refugees were invited to the officer’s quarters for a smoke and a beer, the essentials for every Vietnamese guy. If a meetup didn’t have cigarettes and beer, it wasn’t a meetup.

My dad is certain that if they were on their rickety fishing boat just one day later, they wouldn’t have survived. The day after being rescued, the waves were so furious that he was afraid the sea would have swallowed up their little boat. He even feared these waves were too much for the Ruddbank!

The ship had to dock outside Hong Kong waters so that two refugees with bleeding ulcers and a fractured thigh could be airlifted to the hospital. Meanwhile, the Ruddbank was stocked with more food and water before departing to Shanghai, leaving behind the two hospitalized refugees.

A Two-Year Stop in Japan

Meanwhile, supported by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Japan gave these refugees permission to resettle. After the ship’s intended stop in Shanghai, it sailed to Japan, docking in Mojiko (Moji Port) at the upper tip of Kyushu Island, just across the water from Honshu, Japan’s main island and backbone. My uncle recalled, “Small boats took us from Ruddbank to shore, then onto buses.” He spoke fondly of the vending machines along the rural county roads, whereas my dad didn’t remember anything except a long, long bus ride. The two buses first stopped in Fukuoka, the bustling business center of Kyushu, to be processed as refugees. Then, they were sent to Seibo no Kishi, a convent for Catholic sisters set in the rural backroads of Konagaicho in Nagasaki prefecture.

The refugees would be partaking in Seibo’s tradition of helping those who most needed help. Seibo began as a result of the devastating atomic bomb targeting Nagasaki city. Lots of kids were left without parents. Seibo was founded to provide care and housing for these new orphans. When the orphans grew up, there were no more orphans to take care of, so the sisters refocused their efforts on children with physical and mental disabilities. From the start, Seibo took care of the abandoned ones left behind by society.

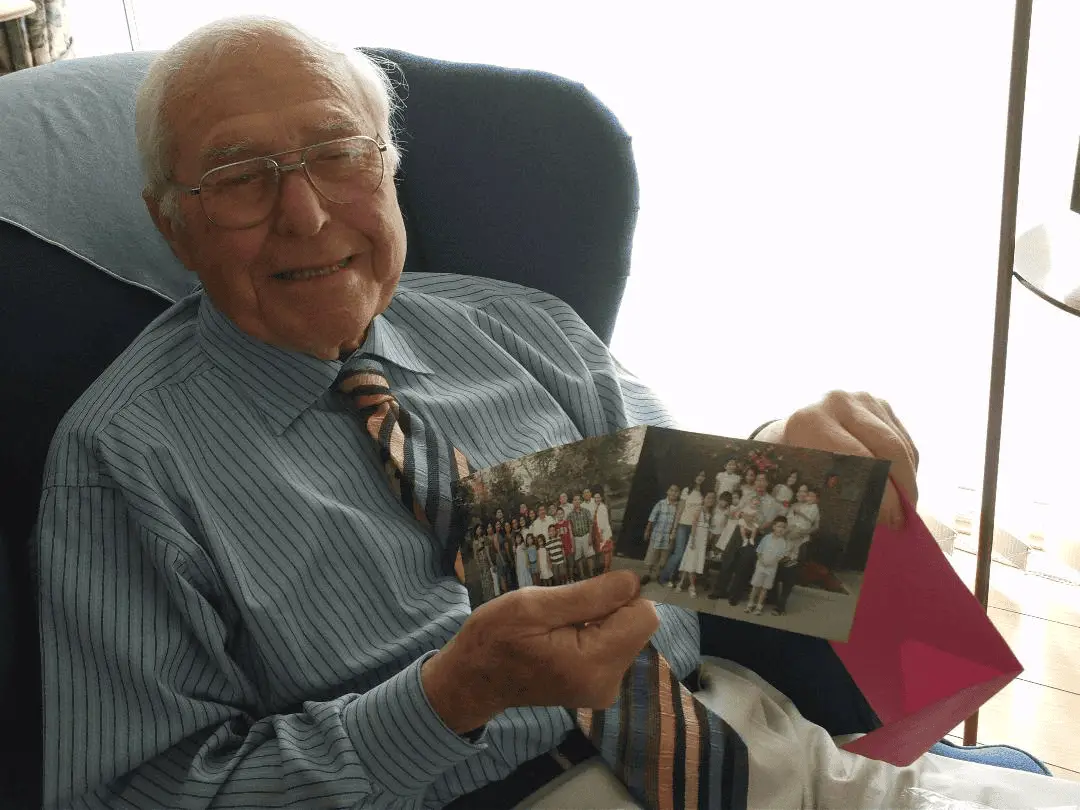

Now, with Vietnamese refugees on their shores, they knew what to do: take them in. They’ve welcomed four waves of Vietnamese refugees, my family being in the second, occurring on September 5, 1979. 44 years later, my dad and I visited Japan to return to the convent so that my dad could relive memories and show appreciation for welcoming him, his brother, and his fellow refugees into a safe place to live. When Vietnamese Sister Nga drove Dad and me to the convent, we were greeted by a group of 20 sisters grinning and waving. Waving back, Dad said, “This is the same kind of welcome I had when I arrived at the convent decades ago.”

The two lead Vietnamese sisters, Nga and Huệ, led us to the pink building where Dad used to live. When we entered his second-story bedroom, he instantly recognized it. He pointed out how he, my uncle, and six other people crammed into this room that was barely big enough for a kid’s bedroom. To save room, they slept parallel to each other on the floor like sardines newly canned from the sea.

My dad and I rested in two bigger bedrooms adjacent to his old room. Resting on that comfortable bed, I felt like an angel ascending into heaven, lying in bed, looking up at the tan wooden ceiling with half-open eyes. The cool November breeze brushed against my skin, a cool, soothing touch. Sunshine streamed its gentle warmth through the window. All was well and at peace in this sanctuary tucked in a Japanese forest.

I left my bed and found a quiet moment by myself in his old bedroom. I laid down on the hard floor, in the exact spot where he slept. As his daughter crossed space and time, continuing the feeling of resting there, in that very moment, I felt a connection with my 20-year-old Dad, as if I were there in 1979. I imagined the crowded bodies and my young dad shuffling around. And then a huge wasp the size of my thumb buzzed into the room, killing the mood. So much for that. That’s when I noticed a big black and yellow spider guarding its web along the walls. Finally, I rescued a gray, triangular-shaped bug by waving it outside, also bigger than the bugs I’m used to. Was this island gigantism at its finest? Was this place Godly blessed?

Staying in the very house that a crowd of refugees used to live in, I felt a bit creeped out at its size. So many toilets, sinks, bedrooms. The metallic mustiness of the bathrooms and the sweet smell of fresh wood surrounding the bedrooms captured me. I knew this was a guesthouse, but it felt largely unused for a while, yet lived in. Between bits of time, people came and left. I tried imagining it to be a more bustling place than it was now. Being empty and unused by people, the house felt so big. Maybe I felt the ghosts of those who had once lived here. Considering how clean yet well-worn the house was, I kept expecting someone to pop into the downstairs greeting room anytime, even though the house belonged to only me and my dad for these two days.

Walking outside with Sister Huệ, who was a young Vietnamese person, she could empathize with the refugees. “Back then, Vietnamese lives were so difficult that nobody really paid attention to the beauty surrounding them. When I started at this convent, I opened my eyes, as if for the first time, to the beauty of the forest and ocean around me. Life is always beautiful.” I was taken aback by the raw beauty of the gentle green hills rolling down to the bright blue waters of the bay. A gentle pink sunset stretched over the bay and opposite strip of land commandeered by mountains. But when my dad was here over 40 years ago, he was blind to this beauty. Taking photos, he said, “I didn’t appreciate this when I was here. I was too busy thinking of my next move, my way out of here.” It had taken 44 years for him to finally enjoy this slice of rural countryside.

In rural Japan, we weren’t expecting dinner with Vietnamese food! Three Vietnamese sisters, Sister Hiệp, Lựu, and Nga (another sister who shared the same name as the leader), cooked comfort food that reminded my dad of home, including rau muống (stir-fried water spinach) and canh chua (sweet and sour soup). Across the steaming plates of food was plenty of banter and cultural exchanges. My dad spoke of his fast-paced life south of Los Angeles while the sisters enthralled us with their ease to secure Vietnamese foods at local grocery stores. In my dad’s time, he would have to yield to only Japanese dishes. So it seemed even rural Japan was connected to global cuisine nowadays. After dinner, my stomach inflated like a balloon ready to pop. So much good, familiar food cooked with love!

At the end of our visit, my dad told me how shocked it felt to be at Seibo as a visitor rather than a refugee. He didn’t get this luxurious treatment (especially the huge spare bedroom and hearty meals) during his residence. Same place, but different time, role, and treatment.

In hindsight, my dad was lucky to have been placed in this refugee sanctuary. I most often hear stories of boat refugees dealing with rancid, unsanitary conditions under tents in Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Overloaded refugee settlements and abusive guards meant that the refugees still had to survive by getting enough food, water, and money. One refugee from the Voices of Vietnamese Boat People compilation named Binh Le stayed in Malaysia’s Pulau Bidong camp, dealing with nasty bathrooms, rotten food, and huge rats that bit his fingers while he was asleep. The refugees may have been stuck there for days, weeks, months, or even years. Did they feel freer there than in Vietnam? Maybe just a little more so. It was a glorified prison where the refugees awaited food and any good news that they would be moved elsewhere. But at least they wouldn’t be dealing with a tight-fisted, corrupt government killing not only lives in reeducation camps but killing any lingering trust in a society scraping for enough food to live.

Meanwhile, my dad’s only real complaint at Seibo was the heater shutting off at night to save money that the United Nations provided to Seibo. Come 9 PM, bundle up in jackets. And maybe sneak down to the kitchen to cook a limitless supply of ramen (something you would envy unless you were a broke college student). Compared to other refugees, my dad and uncle were living large, with a proper bedroom with reliable plumbing, modern infrastructure, and a loving community of nuns in rural seaside heaven in a quiet corner of Japan. But my dad was only seeing these glorious hills and the shining bay for the first time in four decades.

My dad and uncle had to adjust to this new rural life in Japan. For one thing, they had to learn a new language. At that time, English wasn’t commonplace in public places like now. My dad had to study Japanese across three languages: Vietnamese to English to Japanese. My dad was so well-versed in Japanese, he became an interpreter between Japanese and Vietnamese. He even picked up rural country slang!

My dad spent his days working. At the butcher shop, he chased down pigs in wallows of mud. He liked that job better than clementine picking at the farms down the street from Seibo. It was the hardest labor he had ever done. It was exhausting to stand on a ladder all day rather than on solid ground.

No job? The convent had plenty of work. At one point, my dad had the nasty job of cleaning the septic tank (unfortunately, our toilet waste doesn’t magically disappear, as much as we want to believe it). At least he had a friend named Lam who was happy to help him. He was a cold man, but that’s probably why he was cool with cleaning, of all things, a septic tank.

My uncle Thi helped a gardener named Terayama tend to the convent’s gardens. Since the Japanese are meticulous about their gardens, my uncle was running the risk of making them upset with less-than-perfect work. Terayama stuck his fingers up and out of his head, perhaps as a hand gesture in the local culture, as a warning to my uncle.

The refugees also enjoyed leisure trips to the nearest big city, Isahaya. It’s a small city by most standards, but when you’re living in a monastery somewhere over yonder in the hills, it’s a big enough city. My dad and his friends strolled the shopping streets and basked themselves in modern Western culture after years of being forced to close off from any Western media in communist Vietnam. It was Japan where my dad first got a Sony Walkman to listen to new ABBA albums that he had missed out on. Living in Japan was where the refugees could enjoy real life, to enjoy it without worrying that their neighbors could rat them out to authorities for listening to Western media.

Once, the refugees even took a field trip run by the convent to Nagasaki city. He was among the many tourists who have visited the infamous bombing site. During the holidays, the refugees visited the convent’s hospital across the street, where they would celebrate with the patients, including those with Down syndrome. When Dad and I visited the former hospital building, Dad recalled the ground-floor cafeteria, now closed permanently due to a lack of staff, where he and his friends used to get ice cream.

To this day, Seibo still takes care of disabled people left behind by Japanese society. But society is changing. As people have become more accepting of disabilities and governments have encouraged more services, disabled people are being taken care of in the city rather than away in the mountains to be forgotten and out of sight. This meant when I visited in 2023, Seibo only had elderly patients. Because they were old, they couldn’t take care of the tea bushes around the compound anymore. The current generation of sisters had already cut down a lot of tea bushes because they had to take care of them all.

Looking for more traces of the past, my dad asked Sister Nga and Huệ about the local high school where Uncle Thi used to play soccer and volleyball. They led us to the empty concrete grounds down the road. Years ago, the buildings were torn down. There weren’t enough children to keep the school alive. People across Japan are leaving rural villages to answer the call for jobs and opportunities in the city. I worried about the future of this little town, Konagaicho. Perhaps it was a ghost town in the making.

The refugees were Konagaicho’s transient population. They were not allowed to live in Seibo forever. One year after arriving, my dad, my uncle, and one other straggler were transferred to a rural church on the coast on December 17, 1980. It was run by Father Martin Ishikawa, north of the city of Kashiwazaki in Niigata prefecture. This church was for refugees who spent the rest of their lives in Japan. Despite endless searches on the internet and Google Maps, my dad and I couldn’t find a trace of this church. Maybe it didn’t exist anymore. The only trace of its existence was in Seibo’s records office, where we found a document recording the number of people who left the convent and for which destination.

While in Kashiwazaki, my dad worked on piston rings for car companies like Honda and BMW at a Riken manufacturing plant. As he lived his second year in Japan, he resigned to the fate that he might be living there forever, even though he didn’t like it. He faced workplace discrimination, getting paid less than native Japanese. He could’ve moved to other countries that accepted him, like the United Kingdom, which was an option only because the Ruddbank was a British ship. He also could have gone to Canada like his other friends, but he knew that he wouldn’t be given opportunities to go to school and get a professional job. His Canadian friends, to this day, are still working in low-paying labor jobs, unable to move up in education and career. To this day, my dad keeps telling me, “America is the land of opportunity.” It was the only country where immigrants could get a free university education and, thus, better chances of a high-paying professional career. My dad stubbornly stayed in Japan, setting eyes and dreams only on America.

The Move to America (Finally)

He had no word of U.S. sponsorship until everything came suddenly in April 1981. Between the United States Catholic Conference (USCC) and the U.S. embassies in Tokyo and Bangkok, they decided for unknown reasons that he and my uncle would be sponsored by a priest, Father Buchanan (affectionately known as Buck), in Loose Creek, Missouri. But just a week before they were due to arrive, Father Buck became so sick that he could no longer take care of them. That’s when a math professor, Mary Smallwood, in nearby Jefferson City agreed to become their new sponsor.

To my dad, everything about this sponsorship was a blessing. Not only could he move to America, he would be taken care of by a math professor who had the academic connections to give my dad an easy start at the university. Plus, my dad wanted to be an engineer, so Mary’s math background was a perfect match.

Seattle holds a special place in my dad’s heart. It was where his plane landed in April 1981 and, consequently, where he first stood on American soil and a USCC representative directed him onto the next flight. After layovers in Chicago and St. Louis, he finally made it to Columbia Regional Airport. The USCC Missouri leader, Alice Wolters, picked him up in the middle of the night and drove him to Mary’s house in Jefferson City.

Jefferson City (or “Jeff” as it’s known affectionately by locals) is Missouri’s capital city. But just because it’s the state’s political center doesn’t mean it’s a big city. It’s so small that no Interstate highway runs past it. You can only drive to Jeff on small U.S. or state highways. There are few schools, few hospitals, and not a whole lot of places for the family to go for fun besides the State Capitol Building or a local public park to walk around. Locals often drive on the very same streets to get groceries or pick up their kids from school.

Unlike many Vietnamese refugees, my dad didn’t want the comfort of a Vietnamese community in America. When he said he would take advantage of this second chance at life after surviving the boat journey, it meant advancing into American society as much as he could. By living in a small town in central Missouri surrounded by your average American Midwesterner, he could integrate with the American lifestyle quickly. He said that if he were to live around other Vietnamese people, he wouldn’t adapt as easily to the new culture.

And so he plunged himself into rural Missouri life, albeit a rather boring one. As a big city boy, he wasn’t used to a quiet setting. He and my uncle lived their first four months in Mary’s house. My dad had already begun his first week getting ready for college by studying for acceptance tests. He passed his favorite subject, math, with flying colors but struggled with English exams. When he wasn’t prepping for college, he volunteered to fix cars, lawnmowers, and even toasters for Mary’s neighbors. He became known as “that handyman” of the neighborhood.

Because Mary got married a few months later, my dad and uncle moved to the second story above a tailor shop in a house on High Street. It was a downtown main street lined with charming brick homes, the library, boutique shops, local restaurants, and even his university within walking distance. He started at Lincoln University of Missouri, a Historically Black College and University, before finishing his four-year degree at the University of Missouri, also known as Mizzou.

Many Vietnamese people leave their first American city so they can stay in a Vietnamese community or seek better job opportunities. But not my dad. He lived in Missouri for over 20 years to take care of my half-sister. He worked at the same engineering firm the whole time. Though the big-city boy didn’t like the small-town life in Missouri, he still hunted for deer with his father-in-law, picked up redneck slang from his coworkers, and traveled through the backwaters of Missouri on his frequent work trips. He can still tell you how deer jump over fences with a ballerina’s grace and how to get around central Missouri’s state roads.

Not only did my dad’s American story begin in Jeff, but so did his family. I was born in Jeff, along with my half-sister and nephew. Three of my dad’s descended generations were born in this small American town. I don’t remember much about my childhood in Jeff since I was there for only five years and subsequently have lived in different American cities. But life has always taken me back to Jeff so I can visit my sister and nephew.

My dad has spent two-thirds of his life in America, starting at age 21. He assimilated into American life so quickly and deeply that if it weren’t for marrying his second wife, my Vietnamese mom, he might have lost even more of his Vietnamese culture. He has a small regret of not passing down Vietnamese culture to me. He only speaks English to me and almost never shares Vietnamese cultural tidbits. The most I get out of him is the joy we share eating Vietnamese food.

Because of my dad’s sacrifices and risks, I have a life in America where I don’t have to worry about securing a good education and getting food on my plate. I’m in shock that I have a life at all. My dad could’ve been one of the many unfortunate souls who perished on their boat journeys. But because I’ve heard my dad’s boat story so often, I’ve been normalized to it. It’s only when I see other people’s reactions that I realize just how harrowing, incredible, and lucky my family’s story is.

After working so hard in school and then as an engineer for 40 years, he retired in August 2024, enjoying the fruits of his labor. This might look like biking at the beach or fiddling around with gadgets in the yard. Whatever he wants to do. Because he deserves it. I hope he can tell his 20-year-old self that he has come far from surviving that boat journey.

Sources

Thanks to my mom, dad, Uncle Thi, and fellow boat person Hiệu Nhân for the talks we’ve shared.

- Appleyard, H.S. Bank Line and Andrew Weir and Company. World Ship Society, 1985.

- Cargill, Mary Terrell and Jade Quang Huynh. Voices of Vietnamese Boat People. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2000.

- Davies, Charles. “M.V. Ruddbank. Report on Rescue of Vietnamese Refugees From Boat in South China Sea.” 4 Aug. 1979.

- “Record 2,000 boat people are now staying in Japan.” Asahi Evening News, 13 Dec. 1980.”

- “Refugee Entry and Exit Records Provided by Seibo no Kishi.”

- “Two More Rescues.” Unknown author and publication.

- Vo, Nghia M. The Vietnamese Boat People, 1954 and 1975-1992. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006.

How to Airport Travel with the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower Lanyard (Updated 2024)

How to Airport Travel with the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower Lanyard (Updated 2024)