Posted: June 16, 2022

Wafting through the air were the stony scents of hardy brick buildings, heavenly potato dishes, and… poop?!

At the Brontë Parsonage (the home of Wuthering Heights author, Emily Brontë), the piercing reflective shine from curly auburn hair caught my eye. It belonged to a docent named Toria. She specified that I was smelling sheep poop. “After all, this is still a rural area nearby some farms.”

The stench transported me to an unsanitary 1800s Haworth, where sewage freely flowed through the streets of Haworth, as if it could have been its own river. If I thought sheep poop was a stinky, stinky thing, I could imagine the smells of this sewage stream being one hundred times worse.

The sewage polluted local wells of drinking water, which led to a deathly destiny for many people living in Haworth. Sickness and premature deaths were all too common.

The graveyard adjacent to the Brontë Parsonage proves how lucky we all are to not have lived in Haworth during the early 19th century. It is thought that 42,000 bodies have been buried in such a dense space. Tombstones are as close as you can force them to be. And some of the dead had to be placed on top of each other!

As Toria said, “It is not a respectable way to be laid to rest.”

Emily Brontë had it better. Her remains are underneath an interior column of St. Michael’s Church, where her father was a parish priest.

But before that, she supposedly died while resting on a sofa in the Brontë family’s dining room. I imagined the sofa as a deathbed for Emily, its black, wrinkly fabric sending an invitation to die right there and then.

When I first read Wuthering Heights, I was taken aback by how many characters died throughout the novel. One after another, somebody went. But now I understand that death was prevalent in Emily’s community, which so easily made its way into her only novel, published just before her own early death at 30 years old.

One of several notable deaths in Wuthering Heights was of Frances Earnshaw, the significant other of Hindley Earnshaw. Consumption, also known as tuberculosis, resulted in her demise, which left her newborn son with an emotionally abusive father.

Brontë describes Frances’s sickness with great detail:

In the act of saying she thought she should be able to get up to-morrow, a fit of coughing took her—a very slight one—he [Hindley] raised her in his arms; she put her two hands about his neck, her face changed, and she was dead.

How many times did Brontë witness somebody in her community saying that they would be fine the next day — and they ended up dying? How many times did she come across people with coughing spells? How many times did she see a dying or dead person? At least from some of those 42,000 folks now resting in that tight graveyard.

Brontë could have very well been describing the conditions of her own demise — she, too, died of consumption.

But maybe Brontë thought that death wasn’t the final destination.

The main character of Wuthering Heights, Heathcliff, was confident that his love obsession, Catherine, had an afterlife:

You know I was wild after she died; and eternally, from dawn to dawn, praying her to return to me her spirit! I have a strong faith in ghosts: I have a conviction that they can, and do, exist among us!

Even though this was Heathcliff reacting to Catherine’s death, I would like to think that Brontë believed in the afterlife too. She could have been using her Heathcliff character to spread her own message that the dead are always with us. Because Brontë had to deal with an everyday reality of death, she likely needed to cope. There’s something about the dead not being fully dead that might have given Brontë a greater acceptance of death.

When Catherine’s ghost came for a visit to Wuthering Heights, she said,

I’m come home: I’d lost my way on the moor!

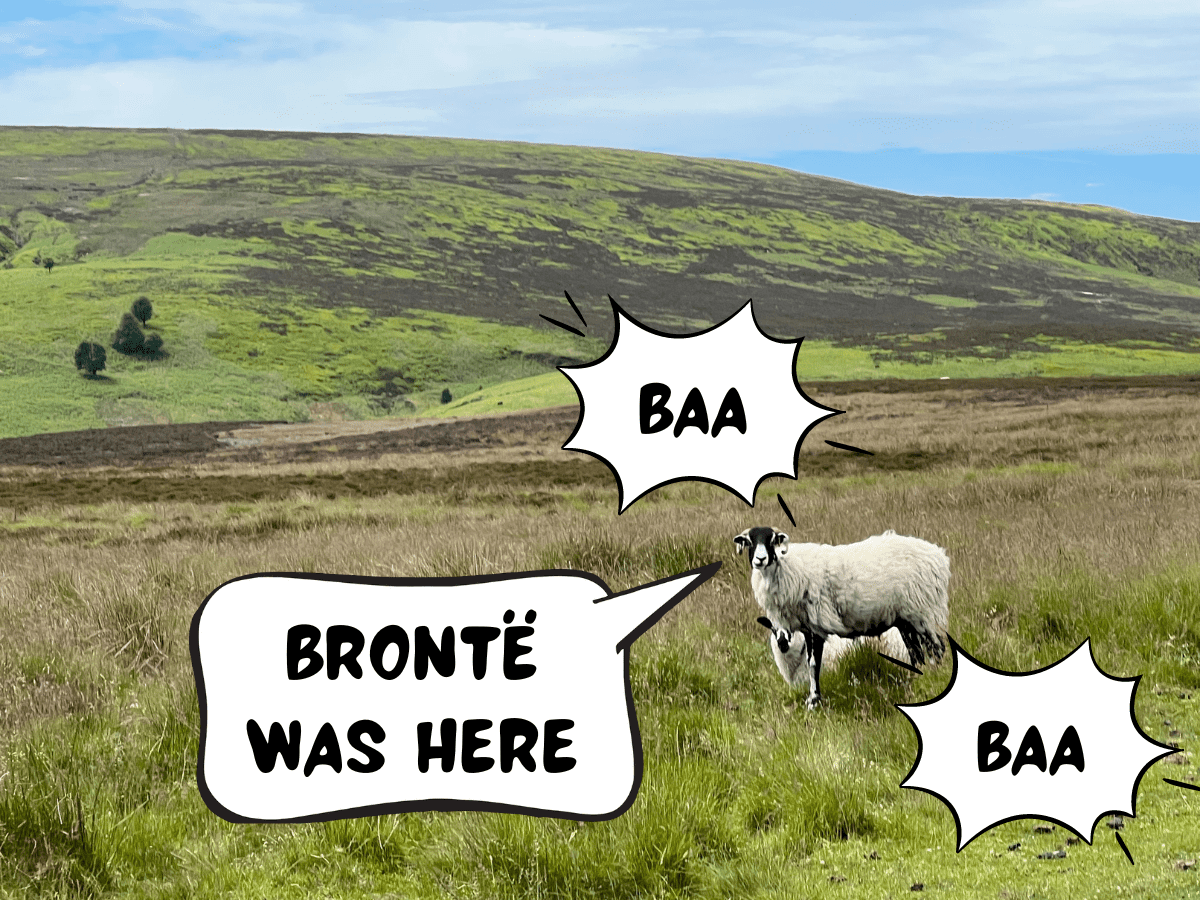

There’s an uncanny feeling that I cannot shake: Was Brontë’s ghost using Catherine’s words to speak to me? When I wandered through the moors nearby the Brontë Parsonage, I could imagine Brontë and her sisters running through its dark purple flowers, laughing, cheering, escaping the village’s deathly reality. For all I know, Brontë could have enjoyed being lost on the moors, where the rules of death didn’t apply in this open field, far away from the coughing, the sick, and the dead.

And the rules still don’t apply.

Because Brontë isn’t fully dead. Her eternal presence can be felt in these fields. The moors will always be hers.

Thank you to the following generous donors for supporting my study abroad trip through a fundraiser:

Janda, Yvonne, Kristina Vorwald, Arianna Samaniego, Tina Kashiwagi, Bac Ngoc & Bac Tuong, Krystal Ramirez, Bac Chi, Melanie, Co Tuyet Anh, Co Be, Co Lan & Co Dao, Co Hang, Annette, Kayla & Brendan, Bac Dung, John Cao, Mike & Jennifer Rumbaugh, Chu Thi and Aunt Janet, Uncle Gordon, Bac Khanh & Bac Thoa, Co Hang Cao, Elizabeth (Liz) & Thai, Jennifer Chapman, Mira Nguyen, Jada Ach, Chu Hao, Ba Gai, Ba Be, Christopher Nguyen, Ba Dung, Steve, Sophia, Maria Martell, Leanna Hall, Heather MacDonald, Mommy, Avagail Lozano, Annie Sisson, Jeff Goins, Unbound Merino.

The Curse of the Creative (England Study Abroad: Week 1)

The Curse of the Creative (England Study Abroad: Week 1)