Posted: April 17, 2022

My first travels as an infant and toddler were because of cancer.

When I think about my grandparents, images of the open road, big skies, and vast deserts flood into me before their faces. As people talk about the good times they have shared with their grandparents, I can’t help but wonder what they must be like.

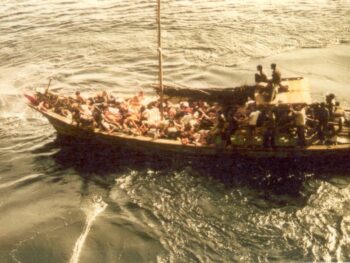

Both of my maternal grandparents died tragic deaths in the motherland due to the Vietnam War’s consequences, long before I existed. As soon as I came onto this planet, my paternal grandmother fell ill to pancreatic cancer. As if the universe wanted to deprive me of the grandparent-grandkid relationship.

It also didn’t help that she lived nearly 1,800 miles, six big states hundreds of miles wide, away from me and my parents. There were only so many car trips we could afford to take to visit her.

Most people begin traveling for fun. But for me, it was forced.

However, my infant brain couldn’t register how serious these trips were. I had no clue my grandma was going to die in a matter of years, and very soon, months. The baby Meggie only thought these road trips were a carefree opportunity to hit the road and see the sights fly by the car window.

Long before I started going to school, I already became aware of how wide the world could be outside of my little Missourian hometown. The open land that seemed to dance with the sky made me feel even smaller than I already was. Grasslands and deserts alike never ended until they eventually made way for another never-ending landscape.

The most “American” part of my Vietnamese-American identity is my seemingly innate lure of the road trip, thanks to the many hours spent on Interstate 40. The Interstate Highway System was inspired by Germany’s high-speed Autobahn highway system and championed by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the 1950s.

History is seeped in the Cold War. The US government wanted improved road infrastructures in case people needed to evacuate cities from Russian nuclear bombing, hence the Interstate Highway System. This same war eventually encouraged the Vietnam War, which led my parents to flee to the United States. Now, we were using the roads that the Cold War worries helped spawn.

I-40 is the fast, modern replacement covering most of the historic Route 66, also known as the Mother Road and the Main Street of America. In its heyday, it connected many American drivers across a large chunk of the country through Illinois, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

Today, Route 66 is surviving by serving up culturally significant old Americana experiences. Old-fashioned diners, themed hotels such as the teepee-styled Wigwam Motel, quirky roadside attractions like the grinning Blue Whale of Catoosa, and souvenir stores selling random knick-knacks — anyone else have a Cline’s Corner Route 66 magnet on their fridge? — along I-40 and surviving parts of Route 66.

Because my family was in a rush to visit Grandma, we stayed on I-40 starting from Springfield, Missouri. Like the modern American, we made no time to stop and enjoy the road as much as we would have liked. I have no memory of stopping, but fragments from photos and stories help. They all seem to come from Arizona, which was a hint that a decade later, I would become an Arizonan resident.

Petrified Forest in Arizona was my first American national park. I have photos of my dad holding baby me in a sea of fossilized tree logs, their colorful gloss dotting the landscape. Though I don’t remember anything about Petrified Forest, I can imagine my parents stretching their legs as they walked around the park, holding me and letting me get the fresh air of the high desert. I find Petrified Forest meaningful for its ability to captivate my parents, even when we were in a rush. Now, Petrified Forest symbolizes the moment whenever I want to stop at a roadside attraction.

The time my uncle tagged along with us on the drive, he wanted us to stop at Arizona’s Meteor Crater, where a gaping hole seems to swallow the orange-brown desert into a sinking center. My parents didn’t think it was worth the expensive admission fee to see a hole in the ground (not everyone would!), so only my photographer uncle visited. Meteor Crater only mattered to me a decade later, when once again, my parents and I stopped by the tourist attraction, but I took the role of my uncle. I was the one who paid the admission fee, while my parents waited in the car once again. Meteor Crater represents the connection between my past and present. I was here as a baby, and now as a teenager who could make my own decisions.

As lonely as a road trip sounds, I had company. My handyman dad duct taped a small, blocky CRT TV in the center console of the van so I could watch VHS tapes of Thomas the Tank Engine and unintentionally develop a British accent thanks to the narrator, Ringo Starr. And then I would peer out the window and see trains in real life, chugging along the road. I even made friends with the truck drivers! When our van passed a truck driver, I would pull my arm up and down to give them a signal, then they honked their blaring horn in response.

Those long stretches on I-40 and Route 66 offered a potty training most kids didn’t endure: the art of peeing in the car and on the road. Whichever was most convenient, we would either pee on the shoulder of the road using the car as a metal bathroom stall with wheels or in a bowl while the car was moving. Every time I peed in the bowl, an unsettling and wide-eyed Bob the Tomato and Larry the Cucumber would gaze at me from the VeggieTales plastic plate covering the bowl. Uhmmm, excuse me??! I wanted to say to the rude vegetables.

At our ultimate destination, the city-infested Santa Ana county in Southern California, my memory fails on me. I can only remember one real-time image of my grandmother: she was sitting in the front-passenger car reaching in the back, feeding me cut-up mango and durian. From her, I first picked up the Vietnamese words for those fruits, respectively, trái xoài and trái sầu riêng. The only memory I have of her is from inside a van. Obviously.

It would only be a matter of time before she died in excruciating pain and got buried under the soil where my family continues to visit her. All the gravestones around her have the faces of the dead, except hers. So I continue to cling onto the memory of seeing her turn back toward me to offer me fruit pieces inside the van, my second home. For most people, durian is a stinky fruit, but I think it tastes good, and it most of all connects me to my grandmother. That’s all I have to hold on.

I’ve done all sorts of travels. Europe by bus. The New York City Greater Area by subway. Countless plane trips.

But being in a personal car on a road trip always opens my heart the most. It is the very foundation of my traveler identity. There is nothing sweeter and more romantic than placing yourself in a land deep in the countryside where mountains, grass, and rivers take ownership of the corner of the planet I happen to be in. And the car will take me there, fostering the adventurer in me.

As a little kid, I already became some kind of badass road warrior! I didn’t get it when most kids complained about their boredom on long car drives. Those kids wanted the trips to end, but I only wanted them to continue until the road ran out.

BONUS! To get more hyped about beginning a road trip, take a journey on Route 66 in the Disney Pixar animated movie, Cars. I’m not even a Disney fan, but this inspirational movie is worth a watch!

How I Sang My Way Through an Agonizing Jungle Hike in Costa Rica

How I Sang My Way Through an Agonizing Jungle Hike in Costa Rica