Posted: April 23, 2021

Even though my face and jet-black hair bear the Vietnamese identity, I still felt like a foreigner in Orange County’s Little Saigon neighborhood, one of the largest Vietnamese communities outside their native country. It sits nearby the California coastline as if to remind the people here that the only thing separating them from the mother country was the expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

But I felt an even greater distance than them, having grown up in little towns of the American Midwest and South with white folks all around.

Now that I live in Southern California with its massive Asian populations, I’ve been trying to reverse my assimilation into white culture by opening my mind to more of my Vietnamese heritage.

Which meant that even though I was never fond of most Vietnamese fast food, much less shopping around town, I tagged along with my parents anyway, my mother leading the pack. My first-generation Vietnamese-American family has always treated their food shopping like a Mission: Impossible assignment without any compromises. Since my mom was shopping for ourselves and our relatives, we galloped to and from multiple stores for certain food items, instead of picking up all the food we needed at one store. Each relative stuck to their preferences, must get this specific food at this specific eatery.

Whenever my family shopped for food, I usually complained to myself about the time dragging on and on. But just recently, I thought of all the years they’ve spent establishing their favorites. They were not only particular but patient.

And so today, I wanted to practice my patience and at the same time, absorb all the cultural heritage I could muster.

But first, we had to get there.

After I drove my parents from our home in Oceanside, San Diego County, to our first Little Saigon fast food stop at the Mr. Baguette bakery for French-inspired baguettes, my dad said, “From here on out, I’d better take over the driving.”

His concerns didn’t surprise me. The people in Little Saigon tended to drive slowly but unpredictably. Drivers may pull out of plaza parking lots onto the main drag at a sluggish pace while cars were heading straight towards them!

Plus, the inadequate parking lot spaces bore the weight of the abundant businesses and swarming customers. It was a mania to find a place to park, feeling like an addicting video game. Cars would keep pouring into the overcrowded, suffocated parking lot and circling around on the hunt for an empty space.

The hectic street scene was an instantaneous reminder that I was still on American turf, just when I started feeling like I was in Vietnam.

With the lens zoomed in, I could view the Vietnamese spirit. I once saw a middle-aged woman with a conical hat strolling along on the sidewalk, back and forth at least three times between her house and the adjacent mass of food storefronts, including a major Vietnamese grocery store, ABC Supermarket. Her silk clothes wavered in the gentle Californian coastal breeze while her hands gripped full plastic grocery bags.

But when I zoomed out, she seemed out of place in this expanse of endless concrete and car traffic. She lived in a neighborhood of blocky American homes surrounded by car-ridden streets, mostly of Toyotas and Hondas. Whereas if she were in Vietnam, she would be plodding along narrow alleyways for foot traffic.

The most telling sign of America was the Asian Model Minority Myth on full display. Arguably the most prevalent stereotype of Asian Americans, it fostered a mindset prioritizing academic achievement and high-paying jobs. Some parents have pressured their children into becoming a doctor, lawyer, or engineer, shoving aside the children’s true skills and dreams.

Many young Asian faces were planted onto streetlight banners running down the neighborhood, showcasing their college academic success and pride. Although my Vietnamese face could’ve seamlessly blended in, I would never allow it — I want to be known for more than my academics. I only hoped that behind these students’ public, grinning faces were their true drive to pursue college and enter their chosen career, unafflicted by the Myth and familial pressure.

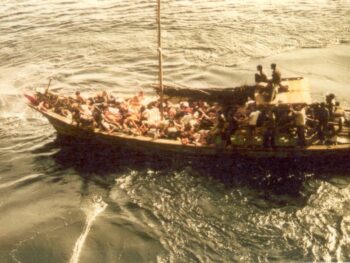

And yet, Little Saigon has been the Vietnamese people’s best attempt at creating their own version of Vietnam on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, piecing together their lives that the Vietnam War stole from them.

After it ended with Communist victory in 1975, many Vietnamese escaped the brutal regime. Camp Pendleton, the West Coast base of the US Marines, accepted over 50,000 Vietnamese refugees. Just north of the base is Orange County, where lots of churches decided to sponsor them. Eventually, many Vietnamese settled in the county’s affordable housing. Entrepreneurs with a vision of creating a gathering space for the displaced took advantage of the abundance of cheap, available land in the city of Westminster, the heart of Little Saigon. And thus, the hub of Vietnamese businesses was established.

Although Little Saigon felt like a haphazard, Americanized reconstruction, it was still everything for the Vietnamese who were forced to flee. This was their Vietnam now, even if it was only a few decades old. Their lives revolved around this humble corner of America, perhaps never needing to set foot outside of it. Their food, stores, language, and neighbors surrounded them as if forming a cloistered sensation of home.

And for me, the best way to experience this new Vietnam was to abandon the streets for warm waiting areas of Vietnamese fast-food restaurants, crammed with customers and food displays. I could keep my lens zoomed in on cuisine.

At various stores, my mom shopped for chả giò (Vietnamese egg rolls), bánh mì thịt (baguette sandwiches with cold cut meat), vịt quay (roast duck), khô bò (Vietnamese beef jerky), and bánh cuốn (rice rolls with ground pork). One whiff of the pungent sauces from the fresh food was enough for me to stop breathing through my nose, as if I were scuba diving into a sea of sharp, oily foods that were made in a hurry. A certain artificial sweetness kept kicking me into the nose. It might have been the MSG that was basked onto many of these delicacies, an unhealthy ingredient that boosts flavor.

The only foods that were a relief for my sense of smell were mild, warm baked goods, including bánh bò (round rice cakes) and my favorite food on this shopping trip, bánh tiêu (a Vietnamese donut caked with sesame seeds). Only upon seeing the columns of bánh tiêu lined behind the glass counter was I starting to get hungry.

My pickiness for Vietnamese food wasn’t the only thing that made me feel like a foreigner, however.

If I tried ordering food by speaking the Vietnamese language, the cashier couldn’t understand me through my American accent. So, my mom translated between my English and everybody else’s Vietnamese.

And I was a human tower, having to bend my neck downward to look at others in the face so that I wouldn’t only see the tops of their black hair.

I felt even taller wearing my signature ballcap with a canyon design that I bought from REI. And I donned a red plaid overshirt like a Canadian wannabe instead of the typical floppy hat and loose flowing shirt.

Even my reading material made me feel foreign. When people around me would open up their Vietnamese newspaper, I pulled out a book about psychology — Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor Frankl, who was a Jewish psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor.

Despite my foreigner presence, I was still a second-generation Vietnamese-American immigrant shopping for local foods with her mother. I was stepping closer towards my cultural roots through food errands. As I grasped in hand the many plastic bags of food, I glimpsed at all the faces surrounding me, which looked like my own, sensing a tinge of belonging.

As we emerged out of the eateries and back into the American world of concrete, the food bags I kept seeing in people’s hands reminded me that Little Saigon was centered on Bolsa Avenue, “Bolsa” meaning “bag” in Spanish. (I was better at translating the Spanish street names than the actual language of my heritage being used around here!) Considering how much food shopping there was in this hub, you’d need all the bags you can get.

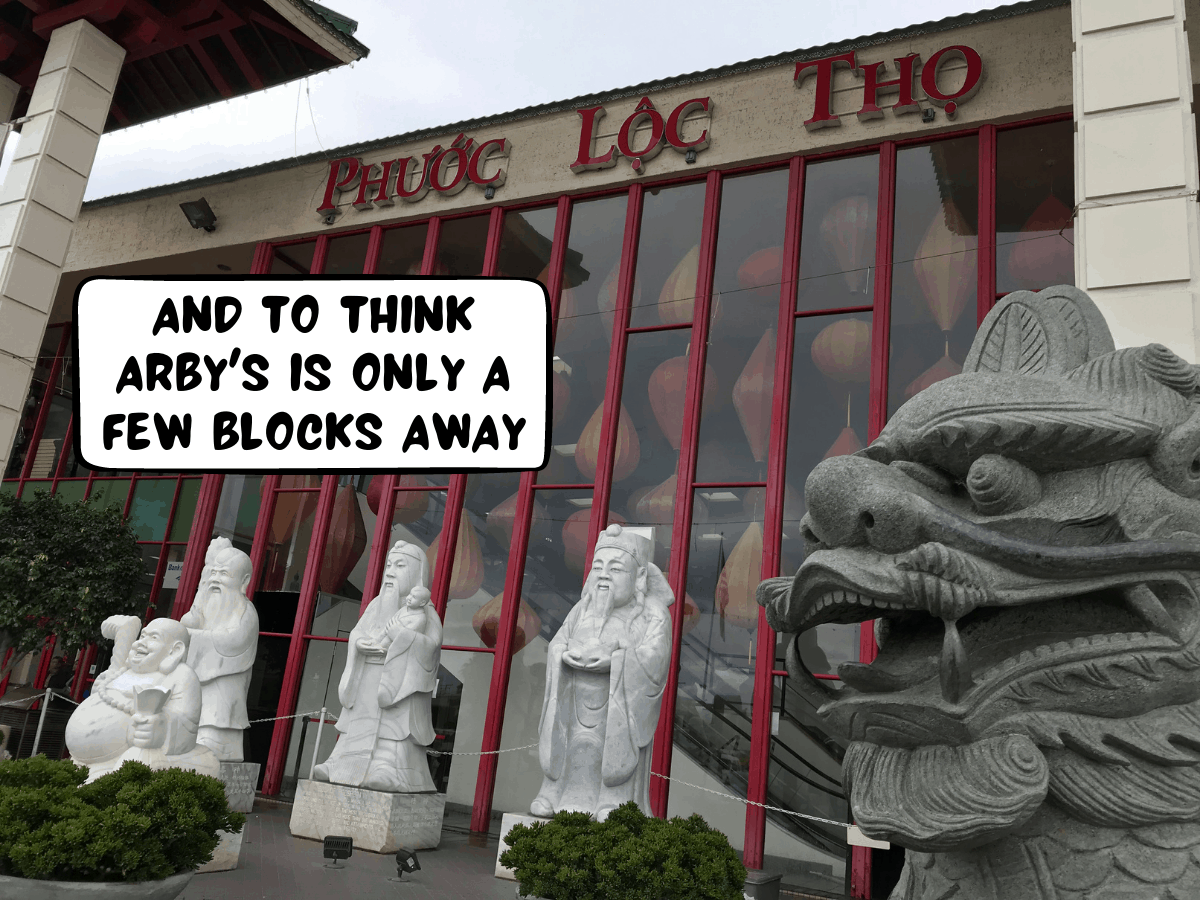

I carried all this bagged Vietnamese food to the car, only to drive a few blocks over so I could indulge in my favorite American fast-food delicacy. Back at our car, while my parents opened their bags of bánh mì thịt sandwiches, I was eating my own meaty sandwich, a half-pound Arby’s roast beef — it always brought me into my nostalgic childhood when I would eat it with my father every Saturday.

Still, I jumped at the chance to eat bánh tiêu Vietnamese donuts, eager for the fried sweetness of the soft bread. I didn’t bother eating the other bread sprinkled with sesame, the bland buns from my Arby’s sandwich.

While waiting for my parents to finish their meals, I sat in the trunk like a pretend vagabond, journaling about these experiences and the current state of my mental health. Writing has always helped ease any tension I held inside my body while on the move. But I still felt exhausted after all the shopping hubbub, driving through town, and food scents that I exposed my nose to — and we weren’t even done yet!

Just before we drove off to more stores, my mom opened her car door to step out and pack some food away, only to have her floppy hat fall off her seat and into a stream of pee — we were too lazy to find a toilet in the shopping plaza. I rocketed into an obnoxious laughter while helping her clean her hat with soap. Now, I was awake, feeling ready once again to continue our shopping errands in Little Saigon and letting more punchy food scents hijack my nose.

Although I still have trouble tolerating new foods, including those of my own culture, I praised my progress. I no longer complained about the food smells or the shopping errands. Instead, I let myself experience the dynamics of life in Little Saigon and even learned the names of the food that my mother purchased.

No matter how foreign I feel, I could count on bánh tiêu donuts to embrace my Vietnamese identity, at the very least.

Share on Pinterest!

4 Healthy Reasons Why Books are the Best Teachers

4 Healthy Reasons Why Books are the Best Teachers